I’ve made it a habit to retweet this once a month or so from Jenn (@DataDiva) who I look up to as a leader in the field of teacher- and student-friendly assessment.

. @emergentmath “Assessment is at its best when it is ongoing and most difficult to distinguish from the teaching that is occurring.”

— Jenn Borgioli (@DataDiva) November 18, 2013

.twt-reply{display:none;}

Citation: Martin-Kniep, G. & Picone-Zocchia, J. (2009) Changing the Way You Teach: Improving the Way Students Learn.

I retweet it because it’s a good reminder and, hey, it’s easy to miss in the never-ending scrawl of twitter. It’s so crucially important that it’s one of those things that should be shouted from the rooftops (on a regular basis, apparently). (PS: anyone know how to get rid of my dumb tweet? I already tried unchecking “remove parent tweet” but to no success.)

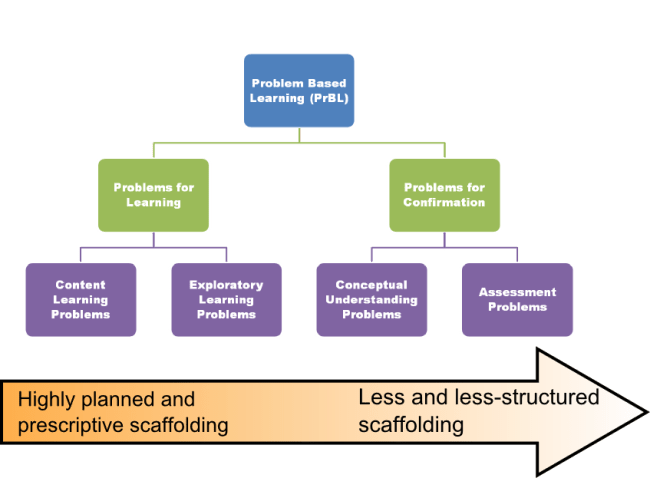

One of the side-benefits of transitioning to an inquiry-based, problem-based classroom is that you can slowly start to scrap those old entire-class-day-killing tests. Ideally, once you’re humming along, the Assessment Problems and Problems for Learning will be largely indistinguishable.

It took me a while to realize the power of this. It wasn’t until my final year of teaching that I have a single task to students for their final exam. Students worked on groups and developed a presentation on how to solve a particular complex task; it was assessed with a rubric, which was exactly how the class was structured throughout the year.

However, I’ll describe one thing I didn’t do that is crucial, but I need to get in to some rubric weeds.

There ought to be two sections for most assessment tools:

One thing I did not do throughout my classes that represents a huge gap in my practice was assessing against common standards of quality (“super-standards” is a term that I just made up that I need to sit with before I start using). I strictly assessed students against the particular content that was being taught at the time. “Demonstrated how this diagram proves Pythagorean’s Theorem? Great! PROFICIENT.” “Failed to simplify the quadratic into its simplest form? DEVELOPING.” What was missing was tracking growth in particular mathematical proficiencies over time. More generalized mathematical proficiencies such as “Developing a model”, “Using mathematical literary conventions”, “Representing scenarios in multple ways” that are ubiquitous across most worthwhile problems. Think Bryan’s Habits of a Mathematician. Shoot, think Common Core Standards of Mathematical Practice. By using indicators that lie outside the realm of the particular content addressed in a problem, students can demonstrate growth over time, and learn what it is to be a mathematician (and probably better articulate it).

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about: the top row is specific to this particular problem, the succeeding rows are to be assessed periodically throughout a course.

But this brings us back to equalizing the assessment and instruction. If these are the things you assess, then these are the things you have to teach. And it has to be ongoing.

Also be sure to check out Raymond’s analysis of Shepherd’s The Role of Assessment in a Learning Culture (2000). From which, I’m going to straight up crib his block quote:

“Good assessment tasks are interchangeable

with good instructional tasks.”